I started flying to Saudi Arabia in 2015. Once a month, every month. After a blur of business class lounges, jet lag that felt less like a time shift and more like a personality change, suitcase roulette, and layovers that defied logic, it somehow turned into a second home. At first, it was all quiet beige corridors, polite silences, and rules that clung like Saudi dust.

There was something spectacular...and almost surreal...about arriving in Riyadh before tourism had touched it. No souvenir shops, no tour groups, no curated experiences. Just the raw, unfiltered rhythm of a city living entirely for itself. We were there not as visitors, but as collaborators. In 2015, we were laying groundwork for public art, urban design, and cultural strategy that hadn’t existed yet, part of the early visioning work that would one day help reshape how the world experiences Saudi cities.

Back then, our coworker Mohammad would meet us at the airport, and the religious police, the mutawa, still had enough presence to make sure my female coworker sat in the back seat. It was just the way things were. No questions, no options.

But over time, something shifted. The country didn’t just change. It cracked open. By late 2019, when the first tourist visas were introduced, Riyadh was already starting to hum with a different kind of energy: open-air art festivals, experimental architecture, cafés filled with young Saudis talking about startups and sustainability. I watched, firsthand, as a city once closed to outsiders began telling its story to the world. And in some small way, I got to help write the prologue.

I remember the first time our Saudi team member picked me up from the hotel. She was driving. That was June 2018. A woman behind the wheel, something that had been illegal just a day before. I still remember the quiet pride on her face. No ceremony. Just motion. Like it had always been that way.

As we drove, she asked me to put on music. I cued up Rage Against the Machine... or what I called them Rage Against the Beige, a hint, maybe, of what was coming. She had never heard real rock music before. She laughed, and cranked it up. The streets of Riyadh had never sounded like that. A few years later, I’d wake up in my NYC apartment to a photo she sent me: her and a group of friends, grinning under stage lights at MDLBEAST Soundstorm, Saudi’s first major music festival. From silence to decibels, just like that.

In 2015, women voted in municipal elections for the first time. That same year, I saw art books wrapped in brown paper, smuggled in like contraband. By 2020, we were installing public sculptures across the city as part of Riyadh Art. Not just bringing art into the public, but making it part of the architecture. Part of the future.

We brought in artists of all backgrounds, identities, and cultures. Saudi, South Asian, North African, European, American. Not to drown out the local scene, but to hold up a mirror. To show that Saudi had something to say. That it wasn’t just catching up. It was rewriting the rules. This wasn’t just about filling space with sculpture. It was about stretching the edges of what was possible. It was a small step toward a larger integration of people and ideas. A preview of a more open, layered society beginning to take shape.

There was a time when even the idea of public art was controversial. Now it’s the largest public art initiative in the world. We found artists tucked away in corners. Painters, sculptors, photographers. Some had never shown their work outside their homes. We gave them a platform. Not just to learn, but to be seen.

The country got louder. Social media exploded. Cafes buzzed with voices that once kept to themselves. I sat in a cinema and watched a film in a public theater in Riyadh for the first time. Men and women in the same room. Not whispering. Just watching.

Art played a role in all of it. In shaping identity. In reclaiming space. In imagining what could come next. There’s no tidy bow to put on a place like this. It’s still in motion. But what I can say is this: I saw a place go from silence to signal. From closed doors to wide open galleries. From "not allowed" to "now showing."

And I’m still watching.

Some of these photographs were taken during my own fieldwork and research across Saudi Arabia, while others capture moments from intense project periods and visits to the Royal Courts, where I had the honor of presenting to HRH Mohammad bin Salman.

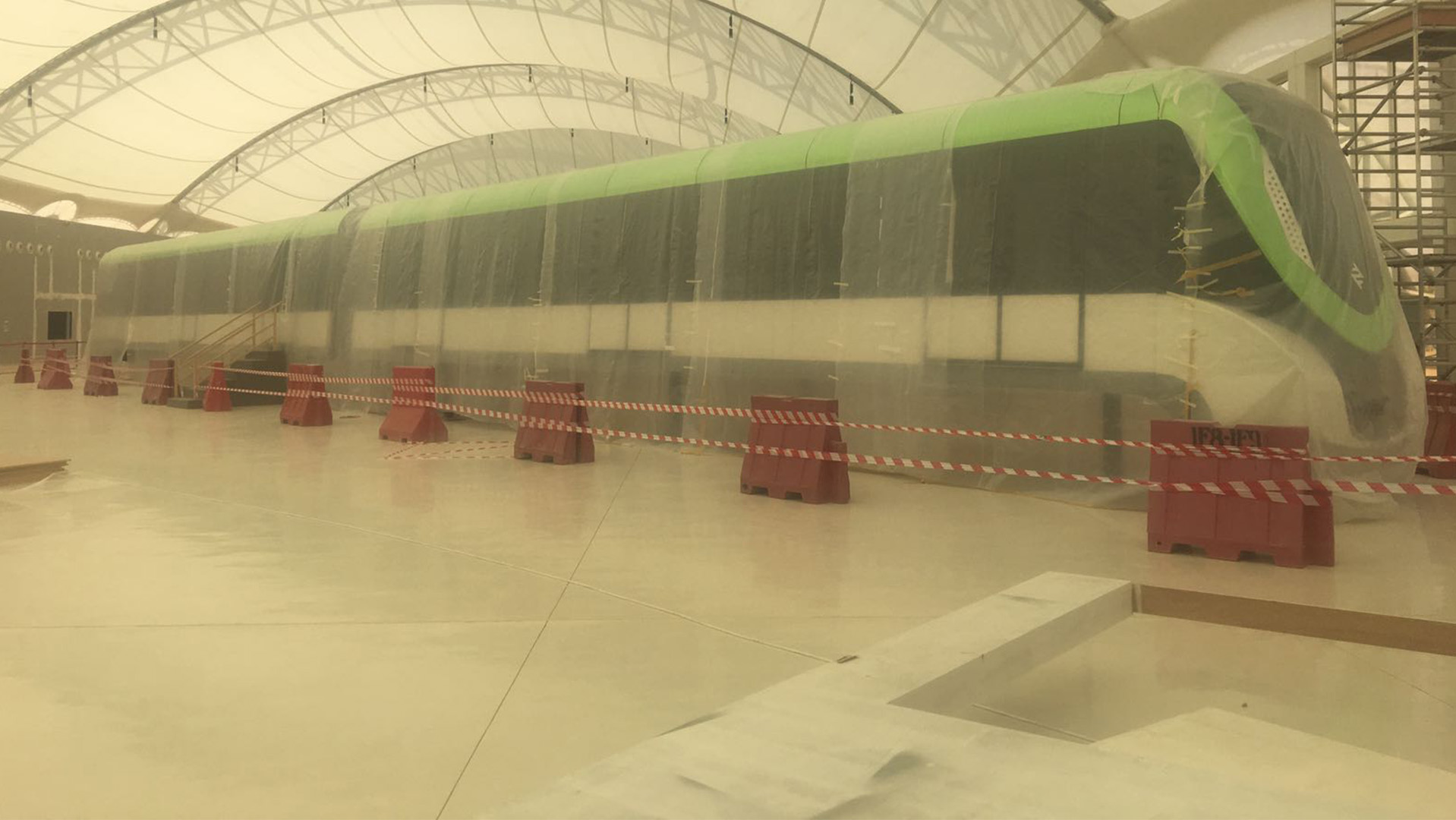

There were countless nights of work that bled into morning. 4 a.m. meetings lit by fluorescent office light. Helicopter rides over raw desert for GSI data. Scrambled flights to Jeddah for eleventh-hour sessions with the Ministry of Finance or the Ministry of Culture. Presentations to the mayor, the head of the RDA, a blur of thobes and bottled water and bullet points.

But there were other days, too. Days spent quading through red sand dunes, camping out under stars by Wadi Hanifa, hiking the cliffs to the “Edge of the World.” Meals cooked over open flame by friends and families who treated us like their own. Camel beauty contests organized by the Qahtani tribe. Shopping at Harrods. Lightning storms that danced across the dunes like something biblical. Dust storms that swallowed the highway whole and made me miss my flight. Late-night laughs over one too many qahwas, the kind that make you forget what country you're in.

I lived out of a suitcase...when it arrived. I missed birthdays. I missed holidays. I missed the people I loved. I was always caught between time zones, chasing signal on dusty site visits, in airport lounges, or the backseat of a taxi barreling through unfamiliar streets. But somehow, despite all the motion, it felt like exactly where I was meant to be.

These photographs were taken on my Sony A7 II, others on an overheated iphone...depending on the day, the moment, or whatever was charged. One day, I’ll find the time to label them all.